Stitching Stories: Harriet Powers and Georgia Quilters

Written by our friends at Athens Heritage Room.

The replica quilt is a reproduction of one of two of Harriet Powers’ well known quilts — the Bible Quilt. You may recognize Harriet Powers’ quilt if you’ve been to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History over the past forty years. Powers’ quilt has been on nearly continuous display from the early 90s to the early 10s, as traced by Kyra E. Hicks in her text This I Accomplish (2009); it is now housed at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

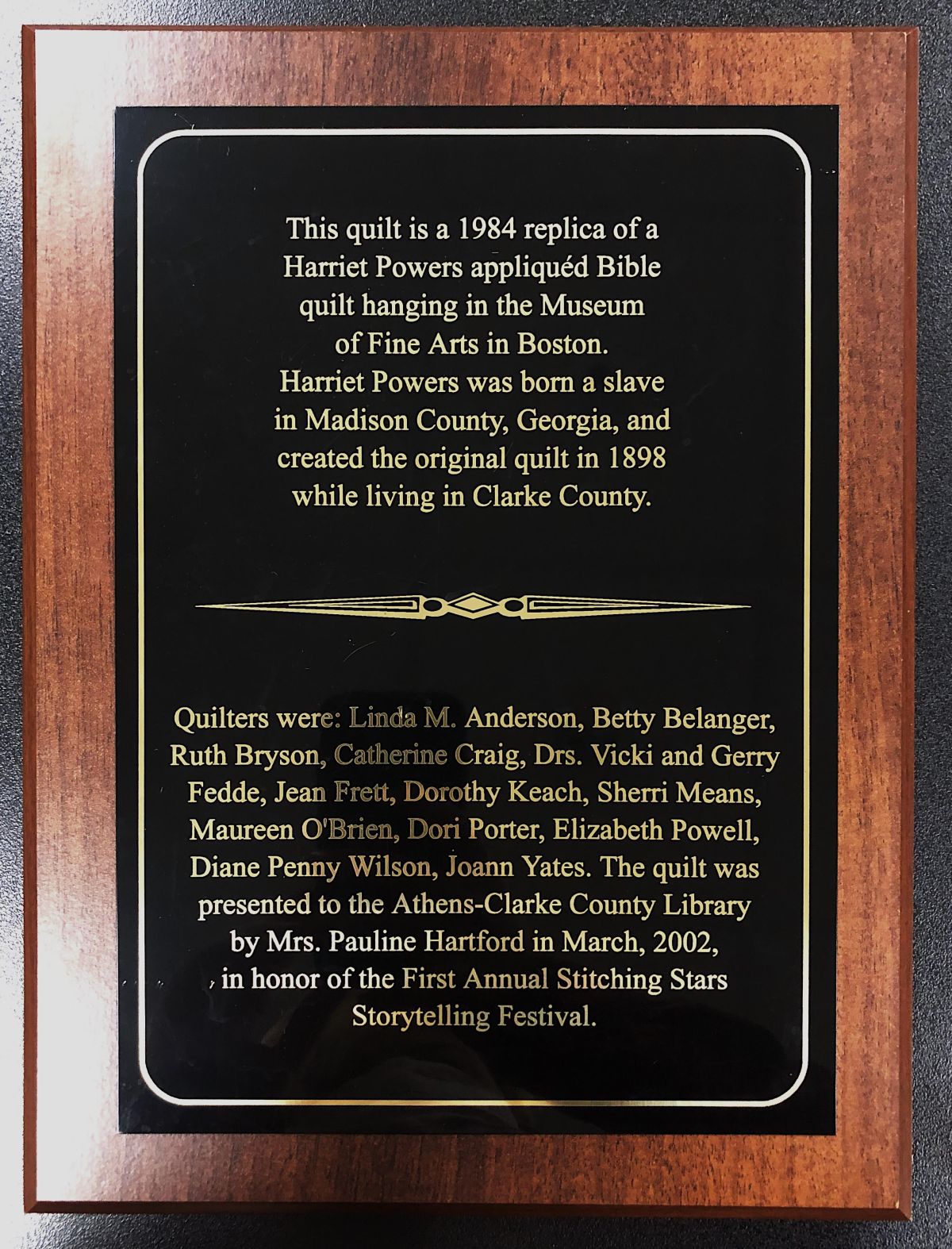

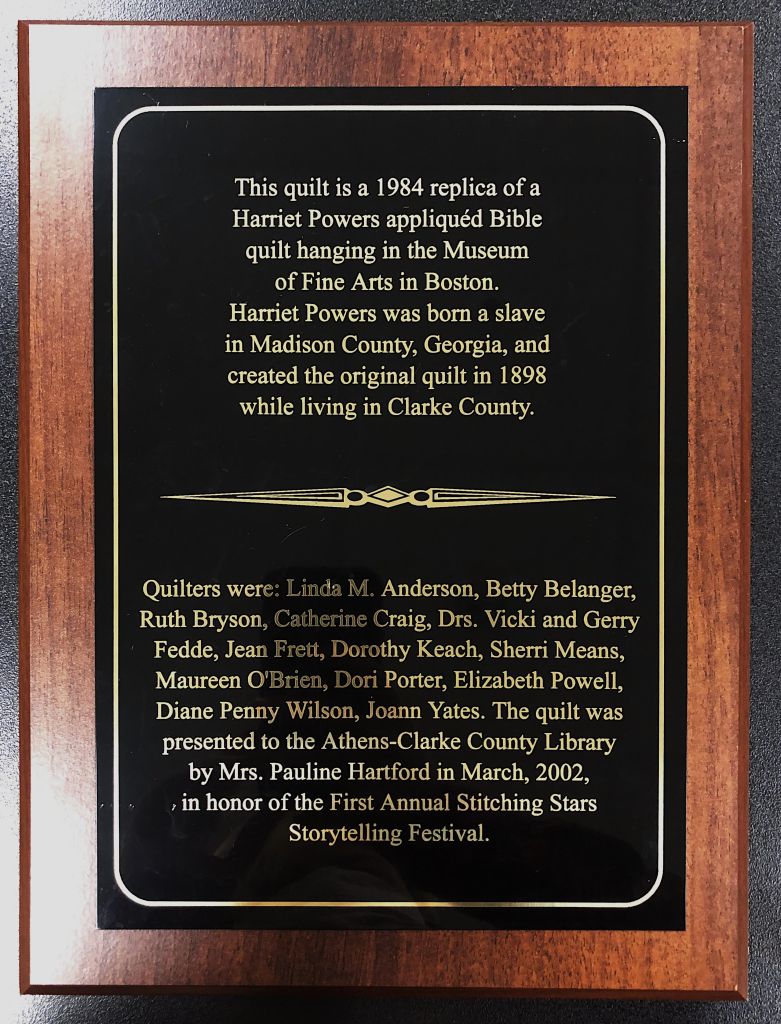

If you’re not looking closely, you may miss the art peppered throughout the Baxter St. library building hidden between shelves and in hallways. All of these pieces are part of the Heritage Room’s Art Collection. The pieces hung up in the building represent a fraction of what we hold, and in today’s blog post I’d like to cover one of the fascinating pieces that has not made it out to display: a replica of Harriet Powers appliqued Bible quilt made in 1984. The original quilt was made by Harriet Powers, an enslaved person born in Madison County in 1837. In her own words, Powers describes herself as “Born in Madison Co. 8 miles from Athens on the Elberton road in the year Oct. 29, 1837” (Powers as cited in Hicks 2009). While enslaved, Powers learned to sew and quickly became a talented quilter. Its replica was made in 1984 and presented to the Athens-Clarke County Library in March 2002 in honor of the First Annual Stitching Stars Storytelling Festival.

Quilting has a long and rich history in Georgian History. In the edited text Georgia Quilts editor Anita Zaleski Weinraub opens the volume by stating that if you were to “ask any Georgian if someone in his or her family made quilts…the answer would be yes almost every time” (Weinraub 1). Quilts tell the story of family history and of small communities throughout Georgia. Weinraub’s editing gives privilege in Georgia Quilts to white communities’ quilts, but dedicates two relevant chapters to “African American Quiltmaking in Georgia,” written by Weinraub, and “The Quilts of Harriet Powers,” written by Catherine L. Holmes. Weinraub reminds readers that enslaved persons were familiar with the sewing and weaving techniques of their homes. Furthermore, some white quilt owners have begun to state that their family quilts were made “with the help of [enslaved persons]” (Weinraub 155, edits my own). Beyond quilts owned by white families, formerly enslaved persons interviewed by the Federal Writers’ Project from 1936-1939 about their living conditions and daily life while enslaved mentioned quilts in passing in more than 50% of the interviews (Weinraub 155).

The replica quilt is a reproduction of one of two of Harriet Powers’ well known quilts — the Bible Quilt. You may recognize Harriet Powers’ quilt if you’ve been to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History over the past forty years. Powers’ quilt has been on nearly continuous display from the early 90s to the early 10s, as traced by Kyra E. Hicks in her text This I Accomplish (2009); the quilt is now housed at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. The Smithsonian further includes a photo image of the quilt on their website.

The quilt features West African appliques — recently historians have noted similarities in design with textiles of Dahomey, West Africa — combined with European stitching (“Georgia Women of Achievement”). The Smithsonian also breaks down the construction of the quilt, noting that “The Bible quilt is both hand- and machine-stitched. There is outline quilting around the motifs and random intersecting straight lines in open spaces. A one-inch border of straight-grain printed cotton is folded over the edges and machine-stitched through all layers” (“National Museum of American History”). Powers’ work was not just beautifully constructed, but told entire stories of works from the Bible. Hicks and the Smithsonian briefly note the subjects of each square to be: “Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, a continuance of Paradise with Eve and a son, Satan amidst the seven stars, Cain killing his brother Abel, Cain goes into the land of Nod to get a wife, Jacob’s dream, the baptism of Christ, the crucifixion, Judas Iscariot and the thirty pieces of silver, the Last Supper, and the Holy Family” (“National Museum of American History”).

Of particular significance to the Bible quilt is the way in which Powers was introduced to the stories that she includes on the quilt. Even as recently as 2009 in her biography written for her induction into the Georgia Women of Achievement biographers have assumed that Powers was unable to read the Bible herself, as seen in this quote from her GWA biography: “Harriet couldn’t have read the Bible, but she heard the oral lessons and sang the songs, and she made the stories come alive on her quilt” (“Georgia Women of Achievement”). Hicks reveals in her 2009 biography of Powers, however, that Powers was literate and self described her schooling as “commenc[ing] to learn at age 11” (Powers as cited in Hicks 2009). Her quilt design demonstrates a power to not just retell Biblical stories, but to interpret them for a new audience. Furthermore, Ms. Powers’ descriptions in her own words are a powerful insight into her own process of quilting. Note, for example, the descriptions she wrote for her Pictorial Quilt:

![The descriptive captions that follow appear exactly as written by Mrs. Powers.

Patterns reduced 58 percent from original size.

1. Job praying for his enemies. Jobs crosses. Jobs coffin.

2. The dark day of May 19, 1780. The seven stars were seen 12. N. in the day. The cattle all went to bed, chickens to roost and the trumpet was blown. The sun went off to a small spot and then to darkness.

3. The serpent lifted up by Mosses and women bringing their children to look upon it to be healed.

4. Adam and Eve in the garden. Eve tempted by the serpent. Adam's rib by which Eve was made. The sun and moon. God's all seeing eye and God's merciful hand.

5. John baptizing Christ and the spirit of God descending and rested upon his shoulder like a dove.

6. Jonah casted over board of the ship and swallowed by a whale. Turtles.

7. God created two of every kind, male and female.

8. The falling of the stars on Nov. 13, 1833. The people were frighten and thought that the end of time had come. God's hand staid the stars. The varmints rushed out of their beds.

9. Two of every kind of animals continued. camels, elephants, [giraffes] lions etc.

10. The angels of wrath and the seven vials. The blood of fornications. Seven headed beast and 10 horns which arose out of the water.

11. Cold thursday, 10. of Feb. 1895. A woman frozen while at prayer. A woman frozen at a gateway. A man with a sack of meal frozen. Isicles formed from the breath of a mule. All blue birds killed. A man frozen at his jug of liquor.

12. The red light night of 1846. A man tolling the bell to notify the people of the wonder. Women, children, and fowls frightened but Gods merciful hand caused no harm to them.

13. Rich people who were taught nothing of God. Bob Johnson and Kate Bell of Virginia. They told their parents to stop the clock at one and to morrow it would strike one and so it did. This was the signal that the had entered everlasting punishment. The independent hog which ran 500 miles from Georgia to Virginia her name was Betts.

14. The creation of animals continues.

15. The crucifixion of Christ between the two thieves. The sun went into darkness. Mary and Martha weeping at his feet. The blood and water run from his right side.](https://accheritageroom.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/harriet-powers-pattern-book-descriptions-4.jpg?w=739)

Powers’ Bible quilt was first exhibited in Clarke County in 1886. The standard provenance of the quilt lists the location of this feature as the Clarke County Cotton Fair; however, Hicks notes that no such fair was reported on in the Athens Banner Watchmen for 1886. Hicks offers an alternative: that Powers displayed her quilt at the Northeast Georgia Fair in the same year. According to Hick’s research, the fair displayed many quilts as over twenty-five quilters were individually named in the paper. Powers’ name was not among them; however, Hicks posits that no African American quilter was mentioned by name in the paper and further reminds us that no African American newspaper existed in 1886 in N.E. Georgia. Hicks also discusses the possibility that Ms. Powers’ quilt was displayed at the “Annual Athens Colored Fairs” which began in 1886. She notes “one local newspaper devoted twenty-two column inches to details…including the noteworthy quilts and other needlearts created by Black women from Athens and surrounding communities” (Hicks 25). The existence of the fair does clearly prove that Black women in Athens were exhibiting their art in the late nineteenth century, despite there being no gallery or museum system open to Black women artists at the time (Hicks 26).

How, then, did the quilt come to be given to the Smithsonian? Kyra Hicks goes through the six people who came into contact with the quilt between Ms. Powers and the Smithsonian. Perhaps the most famous and discussed is Jennie Smith, a white woman in her mid-twenties, watercolor artist, and graduate of Lucy Cobb Institute. Ms. Smith saw the quilt at one of these fairs, probably the Northeast Georgia Fair, and offered to purchase the quilt from Ms. Powers, who declined. Four years later, Ms. Powers was forced by financial hardship to consider selling the quilt. She returned to Ms. Smith and offered it for $10; Ms. Smith was able to give her $5, which Ms. Powers accepted. Thankfully, Ms. Powers explained each of the eleven panels of the design, which Ms. Smith recorded, providing future generations with a narrative of the piece. For more information on how the quilt moved from Ms. Smith to the Smithsonian, consult Kyra Hicks’ informative text.

Ms. Powers is buried in Athens’ Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery; revitalization of the cemetery led to the discovery of her date of death of 1910 on her tombstone as well. She was a talented quilter, wife to Armstead Powers, mother to nine children, and a vital part of Athenian history, and her work remains a fascinating part of the tapestry of Athens art culture. For more information on Harriet Powers, check out the resources below or write a request to the Heritage Room at heritageroomref@athenslibrary.org.

Related Resources:

Interested in finding out more about Harriet Powers? You can read about her in these books from the Athens-Clarke County Library. Some are available in the circulating collection and can be placed on hold and picked up through our curbside delivery program. Others are available in the Heritage Room collection. Our staff is happy to make scans of select pages of books that may be of interest.

Hicks, Kyra E. This I accomplish: Harriet Powers’ bible quilt and other pieces : quilt histories, exhibition lists, annotated bibliography and timeline of a great African american quilter. Black Threads Press, 2009. NONFIC 746.46 HICKS

Lyons, Mary. Stitching stars : the story quilts of Harriet Powers. Aladdin Paperbacks, 1993. JB POWERS

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. A pattern book : based on an appliqué quilt by Mrs. Harriet Powers, American, 19th century. Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 1975. GR 746.46 MUSEUM* (cannot be loaned)